01-05 August 2019

1962

You might have heard this before if you are following our blog. In the summer of 1962 Robert’s family, on the way to or from the relatives in the Veneto, stopped off to see Padua. Robert and Bonnie found the precise spot where the family posed for photos. Kind of neat!

What make Padua Padua?

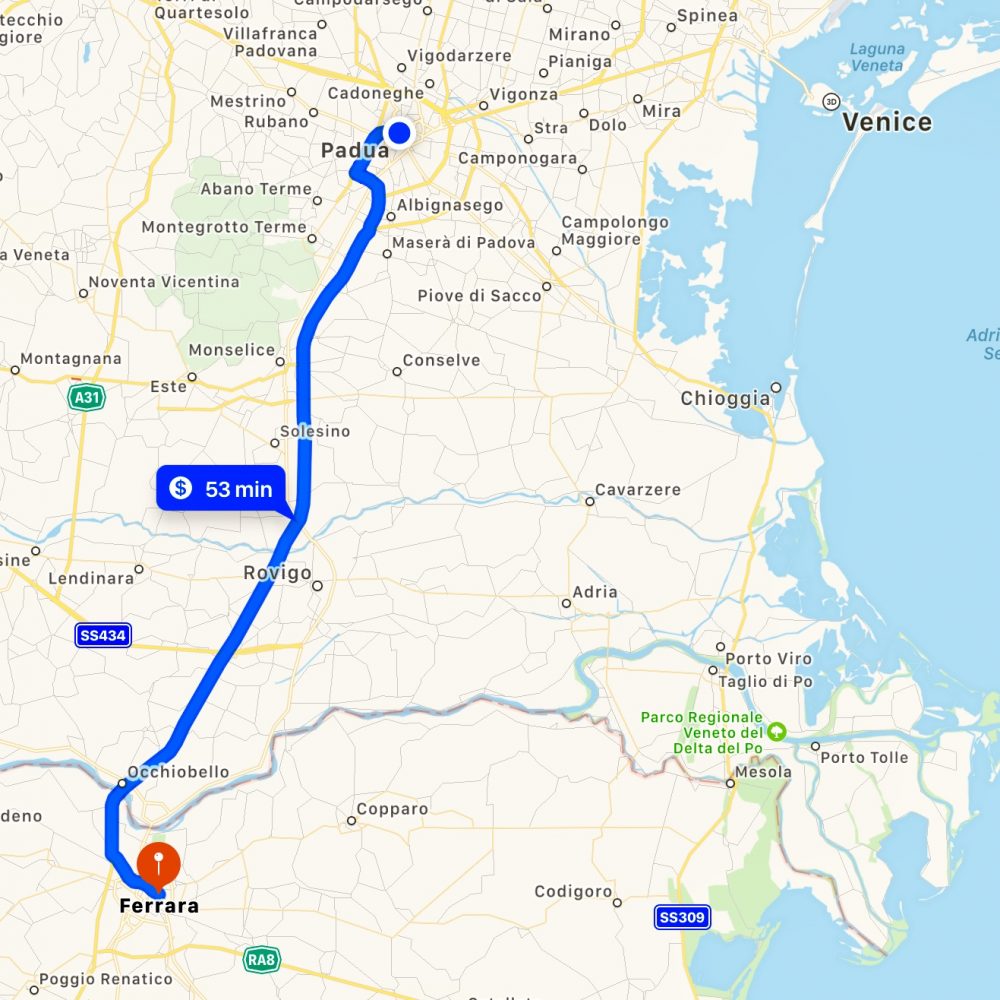

We were talking a few nights ago about what makes Padua different from nearby Ferrara or other Italian towns. What gives it a distinct personality?

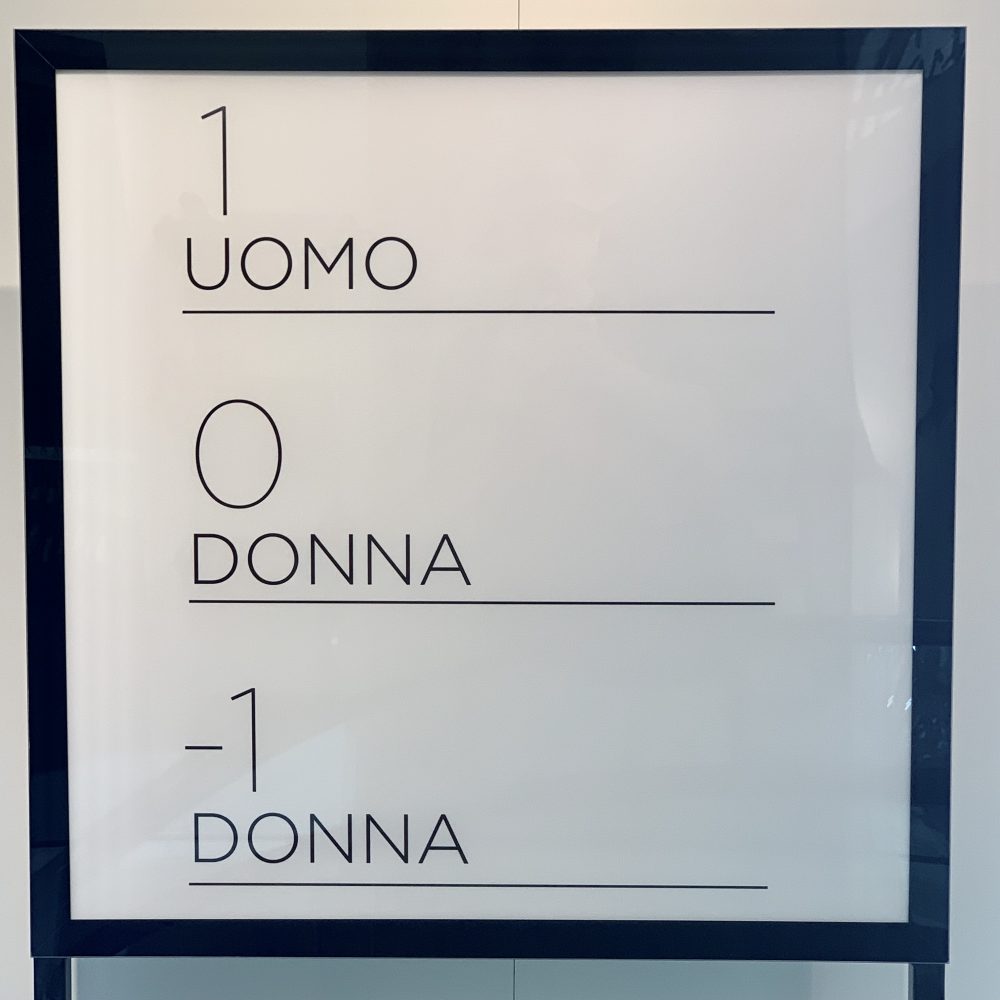

Its population is 200,000, twice that of Ferrara and half that of Bologna, and those differences are obvious. Big Bologna, for example, is populated with nationally and internationally known shops, and it is not easy to find a purely local boutique. Padua also has Zara and Prada and their colleagues, but it also has a healthy population of local shops, selling everything from clothing made on the premises to housewares and hardware. We saw a surprising number of fabric stores. And the area for the food market is big and bustling.

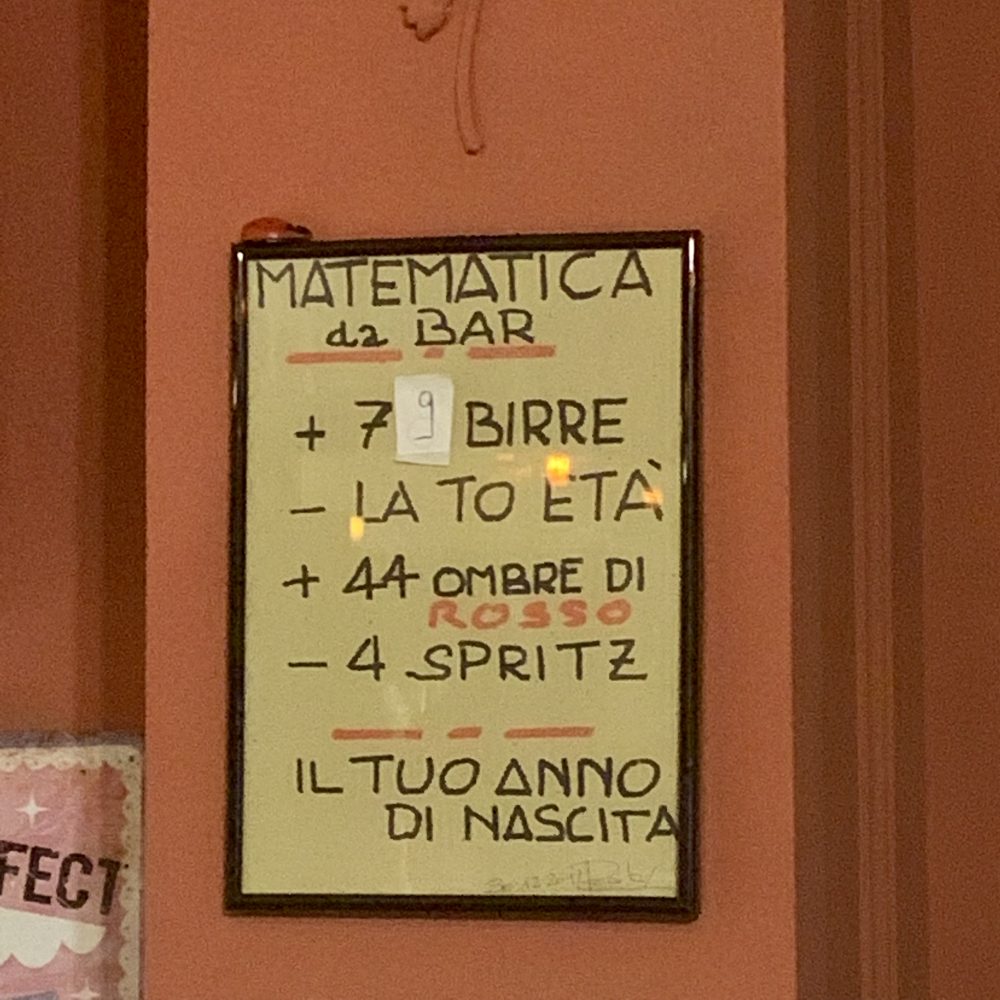

University students in Padua number a whopping 60,000 for the 200,000 residents. Compare this to Bologna, which seems overrun with students, and yet has 80,000 students for 400,000 residents. Surprisingly, we saw few signs of all these students in Padua, probably because of summer break, but the city has the bookstores, man buns, and roller luggage of students, although less tattoos.

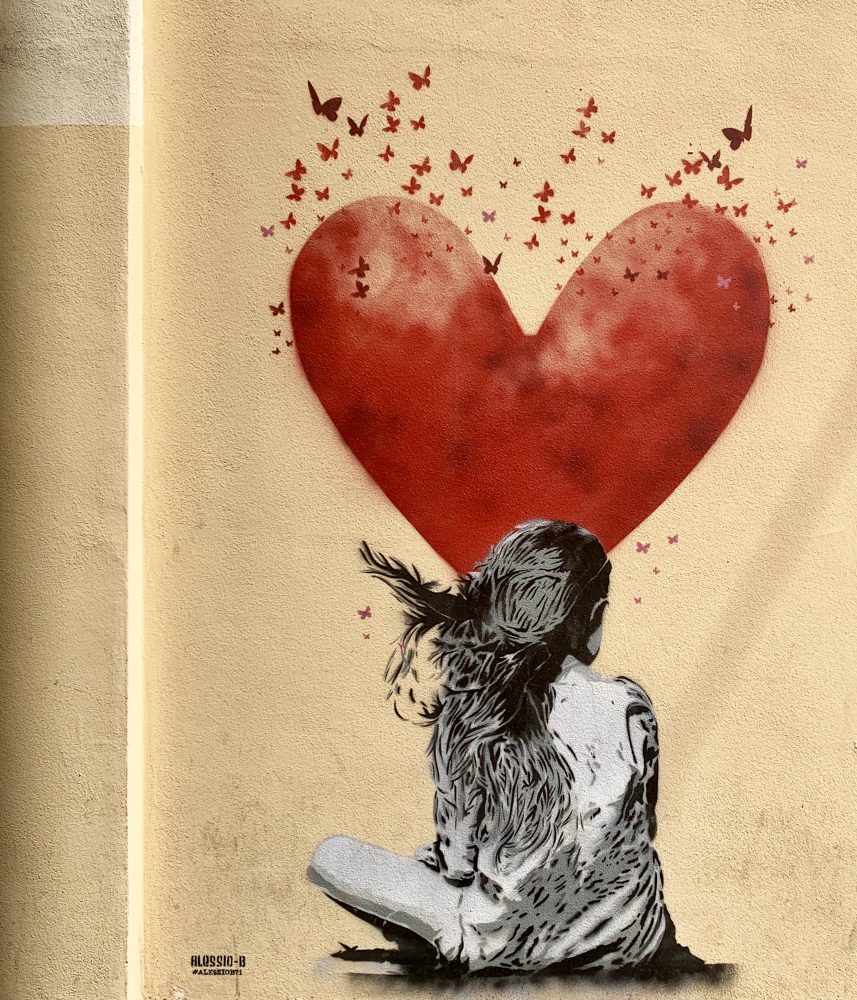

Padua is not as clean and crisp as Ferrara, which is actually a bit sterile. Padua has some graffiti, but not the uber-intensity of Bologna. Padua has plenty of fascinating old buildings but a surprising number of modern buildings as well. We stayed in an apartment in a modern 12-story building a few blocks from the historic center. The city seems to be thriving and not really desperate to freeze its architectural past.

Padua has an extensive network of pedestrian-only streets—more than we have seen recently. This coupled with the narrow streets and locally owned businesses give Padua a comfortable feel. The evening passaggiata is full of people spread over a large area of the city center, mixed with plenty of baby carriages, dogs, scooters, and bicycles. We heard few American voices. More German and French.

There were two notable highlights in our wanderings. The Museo della Padova Ebraica was especially interesting. See the photographs for our experience. And the Cappella degli Scrovegni with frescos by Giotto that all you Art 101 students must have studied (Bonnie and Robert had not) seems to be the most publicized tourist attraction in the city. See the photos for our impressions.

All-in-all, Padua is a nice place to visit. Our three nights and two full days were just right.

Wanderings

Il Prato (Prato delle Valle)

This is the largest square (actually oval) in Italy—90,000 square meters—making it one of the largest in Europe. It shows what you can do, with the needed capital and political wherewithal, to take a large underused and undervalued area and transform it into a unique urban space—in the late 1700s.

Basilica di Sant’Antonio di Padua

No photographs allowed inside. Vast space with the tomb of St. Anthony and artifacts of the saint. Full of tour groups.

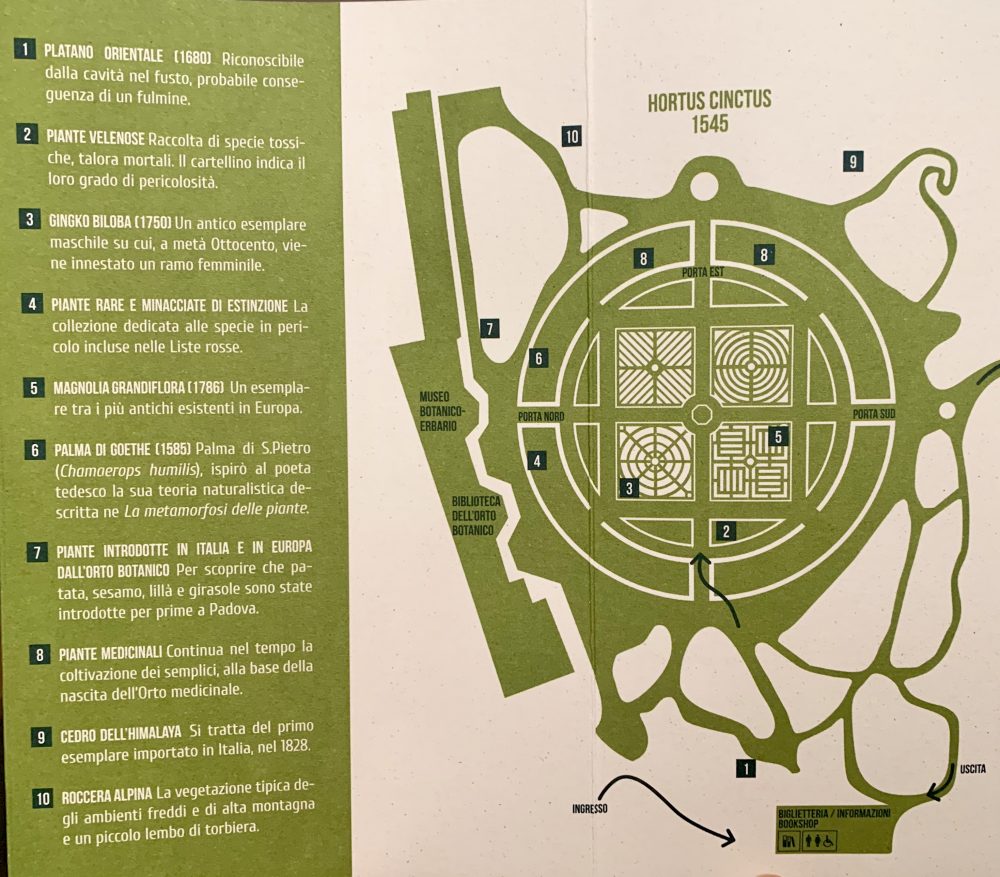

Orto Botanico di Padova

This is the world’s oldest botanical garden in continuous use at its original location. It was begun by the medical school to explore medicinal herbs and is now a UNESCO Heritage site. It is a lovely spot, beautifully maintained.

Scrovegni Chapel

OK art history majors—here goes. The chapel was built by a rich banker, Enrico Scrovegni, to serve as his family’s private place of worship and eventual burial location for he and his wife. (His father, a usurer, shows up in Dante’s Inferno.) The chapel was once connected to the family palazzo, which has since been demolished. To decorate the chapel Scrovegni hired the best of the best, Giotto, who with a team of 40 painted the chapel’s frescos in a two-year period starting in 1303. Giotto was in his late 30s and at the pinnacle of his career.

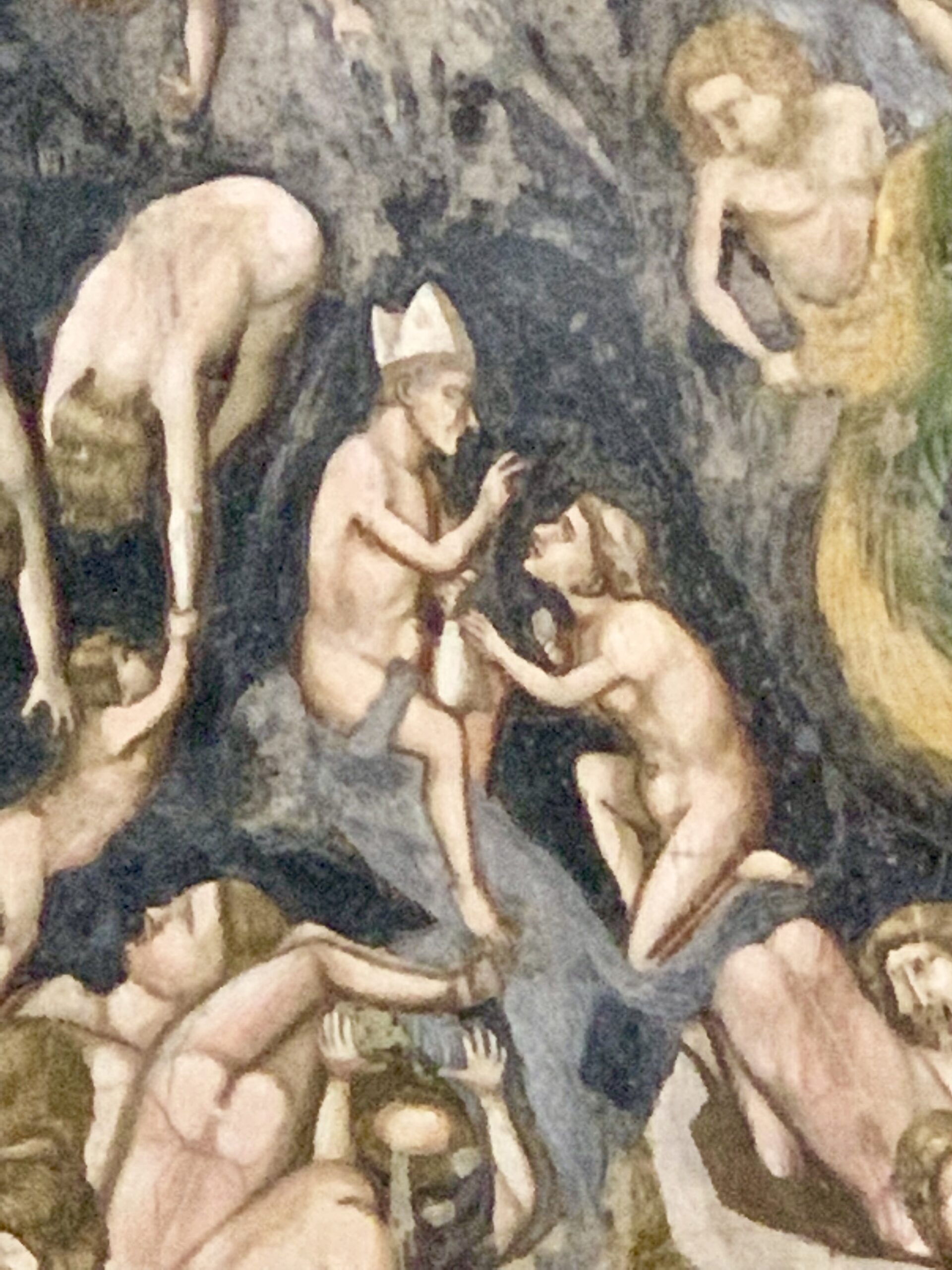

The frescos recount events in the lives of Mary and Jesus. Originally, one entered the church under a large fresco depicting God accepting souls into heaven and sending the other damned souls to hell.

Giotto is known as the painter, who unlike his predecessors, drew his subjects from nature. His paintings depict people in real proportions, often in movement, and with emotional expressions. Before figures were elongated and flat, motionless, and lacked emotional expression.

They give you 15 minutes to view the frescos. So, it is best to arrive prepared to know what you are going to see. The extent of the frescos is quite impressive coupled with the fact of Giotto’s pivotal impact on how to portray the human form. Definitely a must see when you are in Padua.

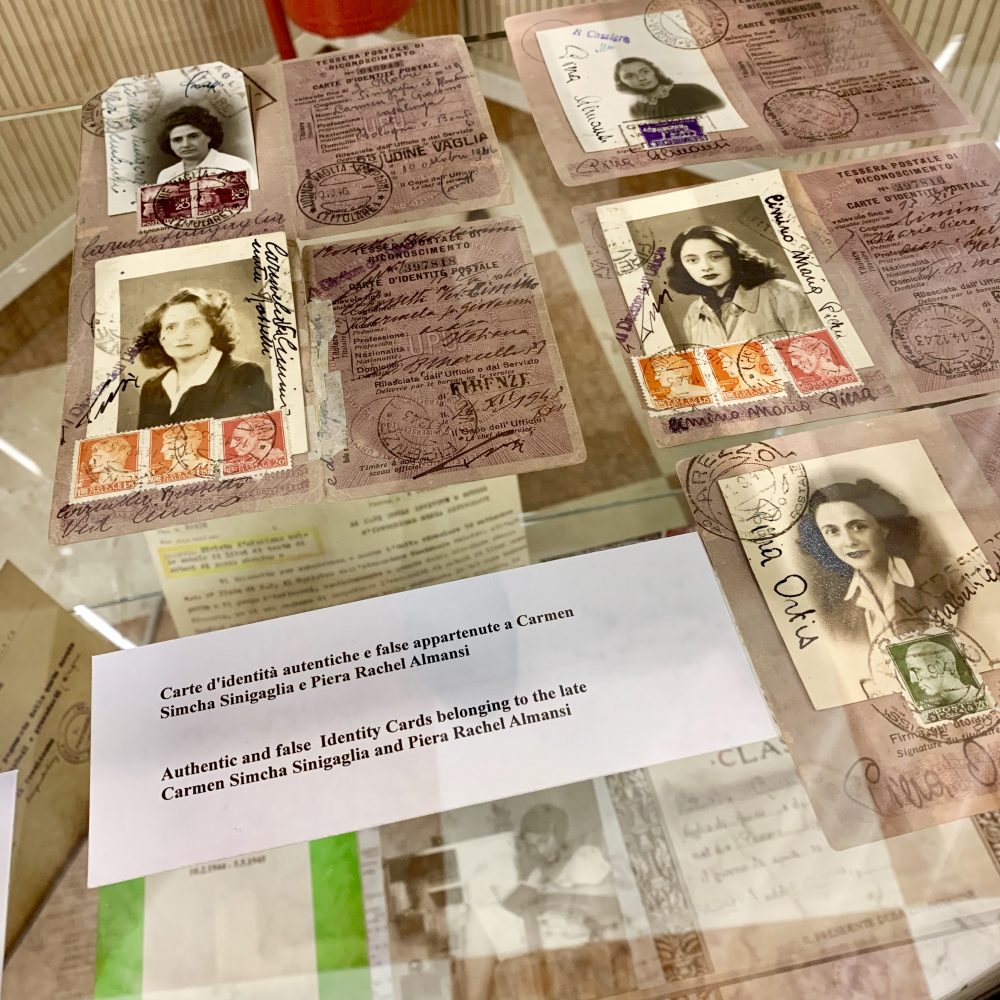

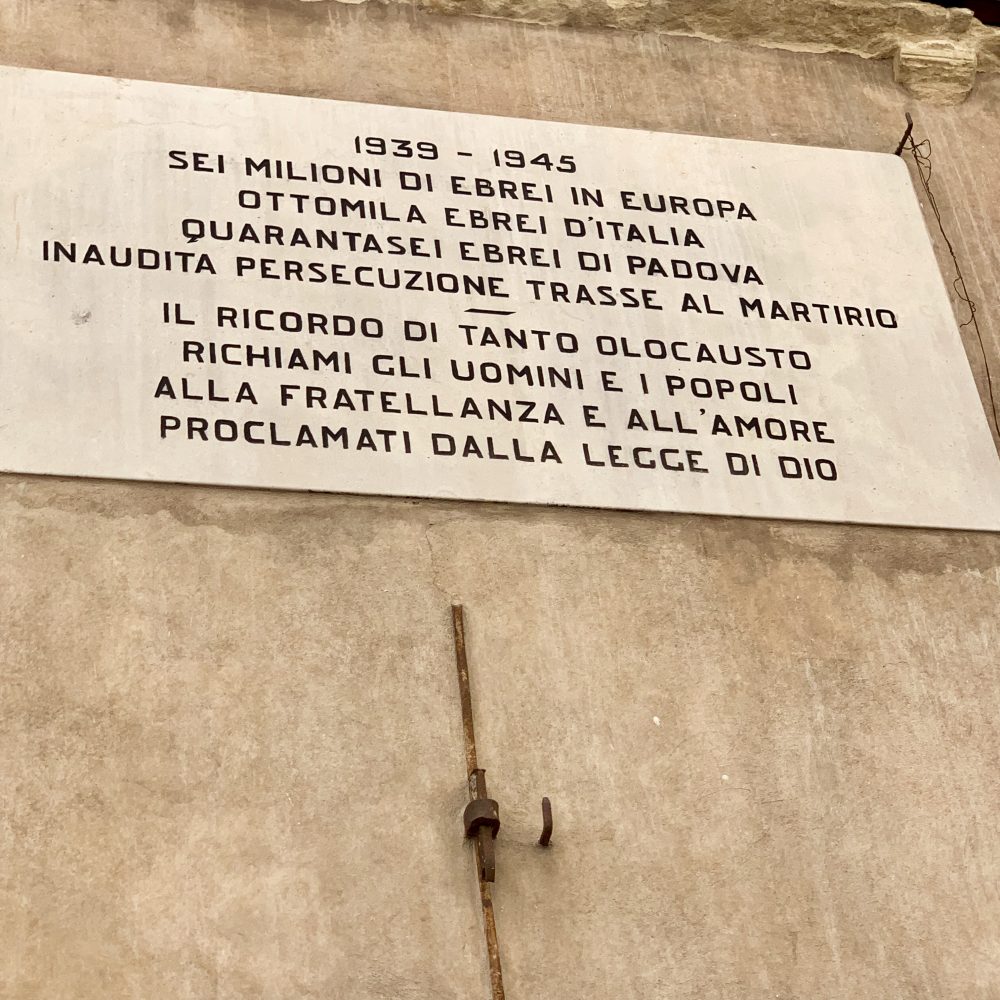

Museo della Padova Ebraica

This turned out to be a lovely surprise for us. We had visited the Jewish museum in Bologna that had an extensive exhibit but lacked any direct connection to the local Jewish community. Not the case here. We were greeted by the ticket seller and another woman, Greta, who personally described the history of Jews in Padova and gave us a tour of the synagogue nearby that is still used today.

Greta emphasized that Jews were always part of the community here, emphasizing that the name of the museum was Padova and the Jews, not the Jewish museum in Padova. She explained that even though the freedom of Jews ebbed and flowed over the centuries, they survived. An example is that at one point they were prohibited from weaving wool, so they went into silk fabrication, which no one else was doing at the time. When prohibited by the Venetians from owning loan banks, they went into businesses. The University of Padova was the only school in Europe to accept both Christians and Jews as medical students, although there was still some discrimination applied to Jews by Christian students.

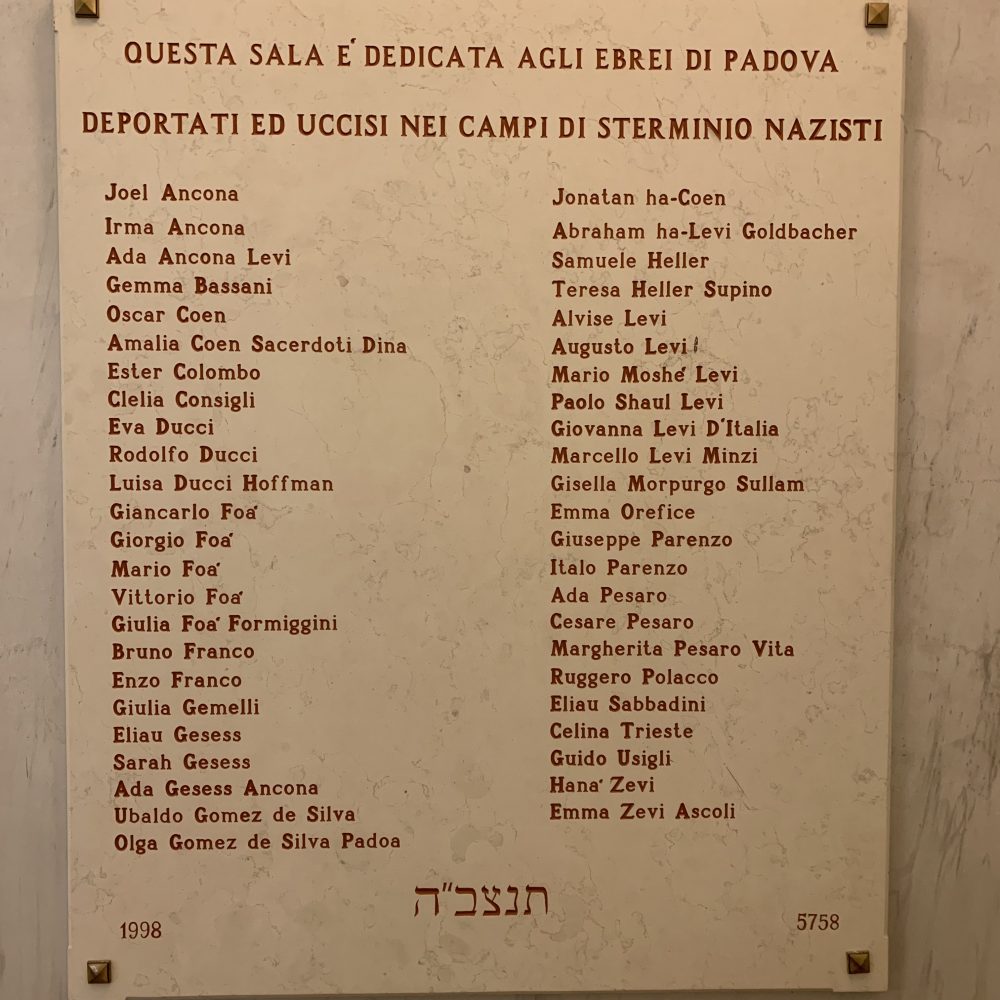

Robert saw the name Sabbadini on a plaque listing Jews from Padua who did not survive the Nazi concentration camps. This is one of several clues that his family might have been Jewish. We have been looking for documentation of his ancestors living in Bologna in the 1200s. Robert now has a contact through the museum for some further research on this family mystery.

Palazzo della Ragione

Chiesa di Santa Maria dei Servi

Art

There is a map of work by serious graffiti artists to locate these and a lot more.

Cibo e bibite

You missed one: Taming of the Shrew set in Padua. Per NYT xword.

JANEo: You must be talking to Bonnie. Not Robert.

Well, yeah!